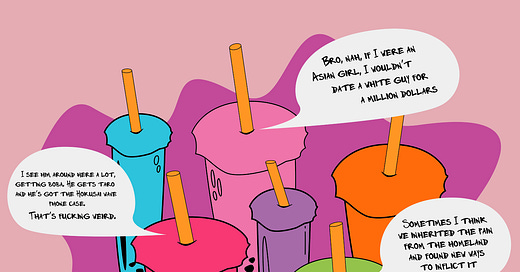

boba liberal romantic tragedy

“But what we do now — Korean barbecue and the boba shop and fish sauce shots — is that so different? Do you like performing this idea of homeland?”

Emily Zheng knew that she met the love of her life as soon as it happened, on a Thursday afternoon, right outside the campus boba shop.

The boba (or bubble tea, depending on your political persuasion), was truthfully just okay here, but it was the only shop that existed within fifteen miles of school, so everyone Emily had ever met ove…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to it's steffi to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.