The streets are saying it’s been a girlhood summer, and the evidence is hard to refute. Between the release of Barbie to the launch of Taylor Swift’s Eras tour, and the evolving label of “girl” trends online — from hot girl walks to girl math — the word feels inescapable at this point. Every viral lifestyle trend is being christened a new brand of girl: clean girl, tomato girl, coconut girl, okokok girl, lalala girl, coastal cowgirl, Lower East Side girls.

“Hot girls are walking, girls are blogging, dinner is girl, forty year old men are baby girls, we are in a girl economy,” YouTuber Mine Le says in a viral TikTok audio captured from her video essay on little girl fashion.

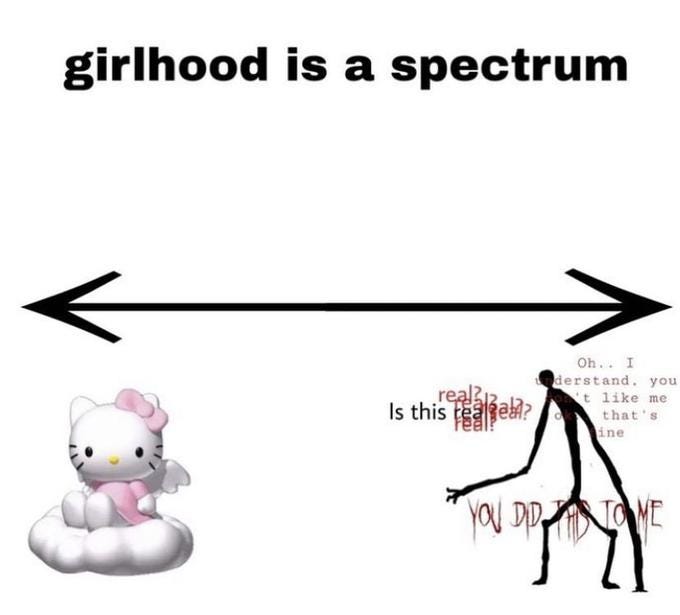

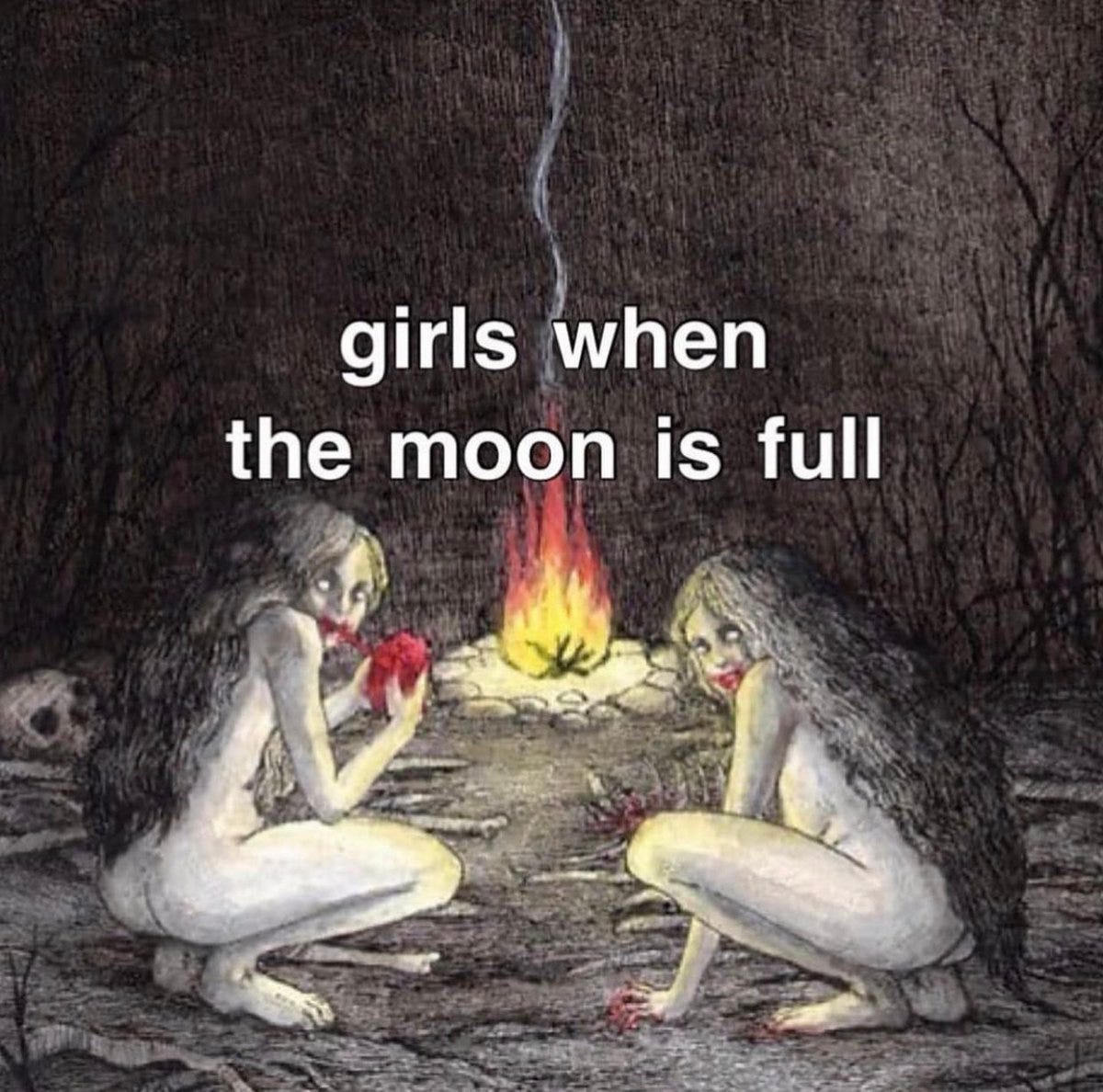

While attempts to understand, dissect, and sell girlhood become increasingly saturated, visually, the lines of what constitutes girlhood have been drawn staunchly across the realms of social media. It’s not just the idea of girls that is so popular, but a whole universe around the identity of who is a girl online. Who is she? Broadly, there is this sort of dichotomy that has split the answer to that question, defined by two general truths: girls are either sweet and harmless, or decrepit and insane. We are either sanitized, smooth babies or we are gremlins, crouched over the sink, furiously gnawing at five cheese strings and a Dr. Pepper that will serve as our girl dinner. We are child or we are animal. There is simply no in between.

One one end of the spectrum, this fantasy of pink, marshmallowy girlhood is symbolized through any number of pastel cartoons, but probably most easily identifiable through Snoopy. On Pinterest, searches for the cartoon have quintupled over the past year, and “snoopy pfp” has become a breakout search on both Pinterest and Google. #snoopy has amassed 1.5 billion views on TikTok, and according to Pinterest, 52% of the users searching for Snoopy on the platform are aged 18 to 24, while 80% identify as women. Snoopy has transcended to a sort of mythic status online, representing a time or space that’s easier, more forgiving and indulgent.

“i say ‘i got that dawg in me’ and it’s snoopy,” one user wrote a June tweet that spawned 15.3 million views and a whole new genre of Snoopy tweets.

There have been about a million thinkpieces about why this end of the girlhood spectrum exists and what these cartoons mean to young women now, but it’s most often attributed as a reaction to the girlboss, girl power, Lean In era of feminism of the 2010s. Now, with continuing global atrocity and general disintegration of society, many argue that this expressed desire to return to a prenatal feminine state is a direct response to the horrors of the world. Snoopy, and this wider genre of softly-colored illustration memes, provide that sense of comfort with nostalgic memory and digestible imagery.

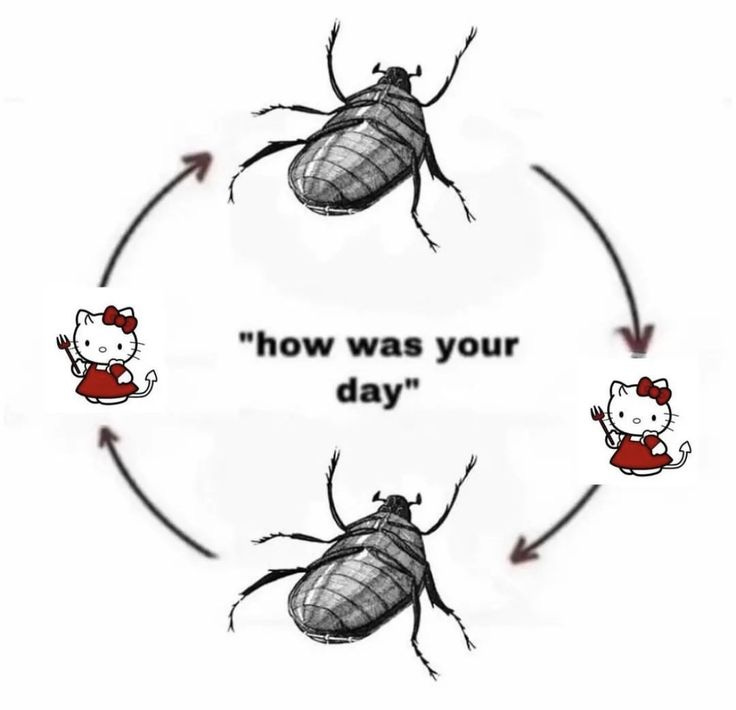

However, on the other end of the spectrum, a genre of content has bloomed to describe an inverse kind of girlhood, one that operates under the visual cues of something raw and animalistic, the most primal part of your mental illness personified. This side of the internet is often seen through its own world of symbols — whether that be black ice coffee, weed, night terrors, ghoulish drawings, Franz Kafka’s Metamorphosis beetle, or most recurringly, the crab rangoon.

The crab rangoon falls succinctly into this category of girlhood because of its sheer depravity. Crab rangoons are a food that are not authentic to any cuisine, not reminiscent of anything, anyplace, or anyone. It is a piece of cream cheese wrapped in deep-fried dough, purely made to satiate our most volatile desires for salt and fat. On social media, they’ve become a motif that has appeared through several different iterations of memes. #crabrangoon has 703.4 million views on TikTok, as people joke about eating crab rangoons as a way to stave off moments of dire mental health. The language of its appearance is very much in the vein that to crave and fully appreciate the taste of a crab rangoon, you must be in a mental state bordering psychosis.

Social media prioritizes hyperbole, so of course the most boiled-down version of identity is what goes viral. This also isn’t the first time we’ve seen these worlds of girlhood split in these realms. Websites like Tumblr were known for their yin-yang of cutesy pink design blogs with an underbelly of deeply unwell themes. The accounts were most often powered by young women searching for identity. That’s intrinsically part of digital culture’s DNA. However with this moment online, where everything is so keen to be labeled as “girl,” it has become increasingly salient to identify these polarities in feminine identity.

Consider Freud’s Madonna–whore complex, which argues that men can only view women through a bifurcation of sexuality and romance: they are either for admiration and adoration as ivory statues, or they are sexually attractive and degraded as whores. “The whole sphere of love in such persons remains divided in the two directions personified in art as sacred and profane (or animal) love,” he writes in On Sexuality. This theory touches on misogyny by way that men are conditioned to innately hate women in a hegemonic society, and how ultimately, women cannot be seen by men as whole individuals, but rather, a mutual exclusivity of object or animal.

Madonna–whore feels reflective of the spectrum of girlhood content online today, from Snoopy to crab rangoons. The Snoopy–crab rangoon complex, if you will. Because it’s not just girls participating in the trend of sharing these images; it’s grown women, who insist that they’re simply teenage girls in their mid twenties, finding solace in these symbols. The reasoning is understandable. As internet culture reporter Rebecca Jennings wrote for Vox:

“More of us are free from the assumption that traditional womanhood is something worth aspiring to. ‘Woman dinner’ is sad; the phrase evokes an image of a tired lady, having already fed her spouse and children, eating the last scraps of whatever was left over before shoving the plates in the dishwasher. Nobody wants to eat ‘woman dinner.’ ‘Girl dinner’ is, crucially, fun.”

But of course to deny the nuance of one’s existence is to ultimately reduce it to lesser than full humanity. And to view one’s own joy as divorced from womanhood has its own baggage. The pitfall of this fever pitch of marketed girlhood comes when women begin to internalize that they are truly incapable of things that children or animalistic creatures have not yet learned — critical thought, reading, research, literary vocabulary, financial independence. Content creator Nikita (@nikitadumptruck), who has amassed 752,600 followers on TikTok for her “girlsplaining” videos that simplify current events into self-described “bimbo” terms, apologized last week for boiling down an explanation of the Palestinian genocide to two girls fighting in the club.

“I don’t know when explaining for girls became explaining for dummies,” said one TikTok user amidst the backlash. “It’s one thing to try and make information accessible, but then to try and dumb down ethnic cleansing, genocide and colonialism…you’re literally disinforming people at this point.”

All this said, I love girl content. I love to go get my little midday treats, to buy my emotional support Sonny Angels, watch fancam after fancam of Snoopy. I love to retweet and repost the memes of haggard ghouls at the foot of my bed, imagining embracing my sleep paralysis demon as a sister. I feel like both of these girls. But as girlhood content hits that oversaturation point, where it becomes more about players in power (rather than grassroots users) branching off of a viral keyword to drive clicks, interactions, and purchases, it becomes more important to understand how this content has shaped our cultural understanding of ourselves. What good is girl content if it ultimately detracts and flattens the true beauty of being women — to better understand and articulate from our unique vantage points, to feel joy in our communities and mobilize our anger, and above all, as Audre Lorde put it, to be powerful and dangerous?